Streets Are For Nobody

The Salvation Army had rescued me two mornings a week from nine to one. They had opened up a day care for homeless parents and I was able to zip in there, put Andrew in the Salvation Army and get down--all the agencies around here in Cambridge, I could go and use their phone. Using phones when you're homeless is a very hard thing. There's nowhere to call from.

I was a go-getter and I believed in God and I had been practicing Zen for several years--my Zen practice helped me to function during my homeless period even though, even with Zen, even with God, it's a terrible place to be--it's a tremendous hardship and it starts to affect you psychologically.

[After fifteen months of homelessness, Diana and her son, Andrew, got an apartment.] So, we got in. Then I went through the depression because we had no furniture, no pots and pans, no nothin', and we were still goin' to the free suppers, and it took us three months to get a bed to sleep in. So it was brand new, what good was it if we had nothin' to sit on, no lights--Reverend Miles brought down candles--lamps are very hard to get used, so, so we were in the dark in more ways than one. After a person stops being homeless, the workers and the people that supported you and the little bit of good energy you were gettin' from 'em, they say, "Oh, she got an apartment, he got an apartment," and they sorta drop ya, not intentional, but it's just that your crisis is over, but we had the crisis of being faced with having to furnish this apartment, everything down to the silverware, and the stress that you have, because, see, you already have an accumulation of stress and you didn't have any counseling--because a homeless person has to do A LOT to get a place. They have to pick themselves up outa the mud--by their bootstraps, you know.

Diana Paliotto. Interviewed in her apartment, Cambridge. 1989.

Um - let's start from the beginning. I'm one outa ten children and, um - life for me was just real difficult growin'. I come from an alcoholic background and a lotta abuse and a lotta sexual abuse. It was very hard for me growin' up because, um, my mother gave me up at age twelve and, um, I got pregnant at age twelve and - here I was a baby havin' a baby - and, um, it was just real difficult for me just to deal with life in general.

Um, a lotta my life is just a lotta old resentment, a lotta hurts, and a lotta pain, you know - Why this? Why my mother gave me up? Why I had to have a daughter at twelve? I didn't ask for a bad deal. I just wanted a mother and a father, someone that could love me and I could love 'em back and have a chance in life. So, there was no God for me neither, you know, because how does God they call a lovin' God give me this kinda life to start with, you know?

Back then, when I was growin' up, it was really in a closet - because you weren't allowed to talk about these things and if you did, you were a bad person because you're not supposed to put your family down, you're just supposed to honor your family, and - you had to sacrifice yourself. For a lot of Hispanic background culture, their culture is you deal with your problems in your house and you don't tell nobody and if you do, SHH, you know, how dare you? You get slapped--you know--get punished, so how were you gonna come out with these issues?

I seen--so many women leave this [half-way] house and I know how painful it is and I know they're all good women, but they just have a - a common disease that if you don't stay on top of it, it will take you, so you have no room for play. It's really serious recovery and that's why I tell you I don't have the feeling to laugh as I want, to laugh and play as I want 'cause today it's my life--this is no game, you know. So if God let me to see the pain for this whole year and let me walk through what I need to walk through, that's gonna be good for me 'cause I might be one outa thirty-seven women that make it outa the treatment--but I have to hold onto that 1/37, you know, 'cause they say that only one people outa thirty seven make it. For me, I'm that one. I was that one outa Long Island Shelter. I was one outa that STAIR Program.

And I will be one outa the Shepherd House, you know. I have some dreams today that I didn't have before. I believe that in spite of my background or where I came from or where my addiction took me and all of that - combined, I believe there's still hope for me that I could change that around. This program have given me that - 'cause I didn't have none of this hope before, you know.

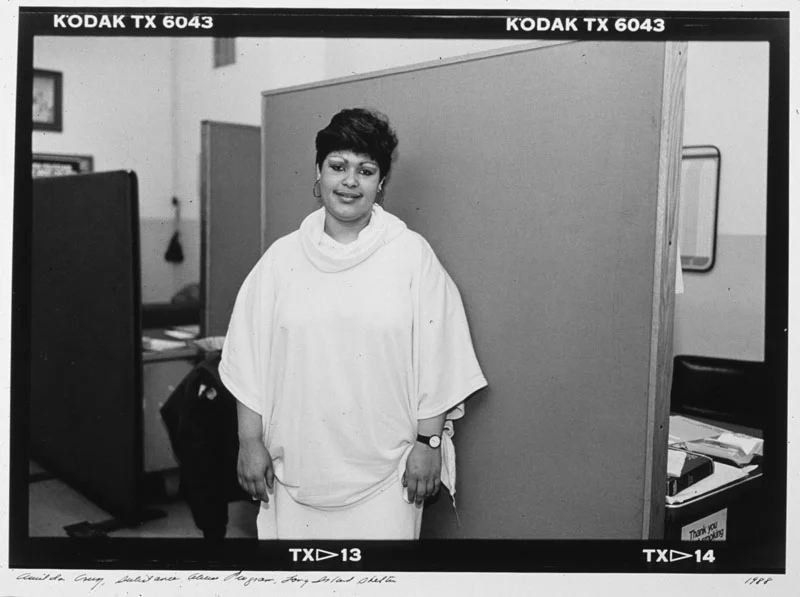

Awilda Cruz. Interviewed at Shepherd House, Dorchester. 1989. She now has her two children back in her life, a supportive relationship, an apartment and a job working with women in need. She is starting higher education.

When I was back on Pine Street--there was one of the psych nurses over there and I was talkin' to 'im one day. He had asked me how I felt towards Trish and I said to him, "Can you describe to me what is the feeling beyond love. Describe it to me. All right?"

He says, "What do you mean?"

I says, "Well, okay, we know that beyond a certain amount of numbers there's infinity or somethin' like that."

He said, "Yuh."

I said, "Now, we know beyond the earth is another galaxy."

He says, "Yuh."

I says, "Okay. So now what's beyond love? When you can come up and tell me what is beyond love, then you will know exactly how I felt towards that girl. And even though she's gone and everything else, that is still the way I feel about her today."

And to be perfectly honest with you, Melissa, as far as I'm concerned, to show you how strong her spirit is in me, right, as far as I'm concerned, this girl is right in thi-this room right now and will always be everywhere I go. Now, you want to call that nuts or whatever you want, but that - that's the way I feel about it.

If it wasn't for her, I would never come outa the shell that I was in. Because I was always afraid of bein' hurt. Now - after I met her, she got me outa the shell and I feel that by her dying - was - I don't know if this is the right terminology to use for it, but - was sort of a test to see if I would go back into that shell or not - because of her positive attitude on--towards me and everything else, I've got no intentions of goin' back in that shell. No intentions whatsoever.

Harry Rubin. Interviewed in his room at Paul Sullivan Trust. 1989. He has a steady job. His wife, Trish, died in 1989 of pneumocystis pneumonia.

Melissa: You stayed out on the back porches?

MM: Yeah. And the front porches, too. We didn't dare go inside because sometimes there was no floor. You were lucky to see the door open but you were afraid that there was no floor, you could step and then go down to the no man's land--kill yourself, probably. It's a wonder those fellas that was drinkin' didn't get hurt.

M: Was there a whole group of you or was it just you and Dad?

MM: No. Dad [Tom] and I, and there's another lady - and her friend there. They kept arguin' so much, I'd say, "The police are gonna come here, so just calm down a little so they won't, you know, come there." And after a while, some fellas found out we were there and they used to come and - yell and holler. So, I said, "We'd better get outa here again, let them stay here." So, we moved to another place.

I used to go to the priest's house all the time and get food for Dad and I - or we'd starve. I liked to make sure that he ate 'cause I knew I could take it, but (I could) see that he was gettin' weaker and weaker - oh, we gotta do somethin' about him.

M: Were you worried about him?

MM: Oh, yuh, afraid that I might find him dead beside me somethin'--but he had to go to a house of shelter - pick Pine Street - cause he was losin' weight--he was sick. So they took 'im.

M: Must have been a hard life.

MM: But I'd do it all over again if I had him.

M: How come you went right to work at Pine Street, Millie?

MM: I don't know. I asked 'em if I could work there. After a short time, they said, "Would you like to work here?" I said, "Sure. I love to make beds." They said, "Make beds? We need you." I like to make beds. A lotta them don't, but I do. (Laughs.)

M: Tell me a little bit about Pine Street, what it's like living at Pine Street.

MI: Beautiful. I like strippin', I mean, the beds. I'll be makin' those beds till I'm a hundred.

M: Were you afraid when you were out on the streets?

MM: No.

M: Were times different then? Was it less dangerous?

MM: Oh, sure, if you'd meet somebody, they'd say, "Hi. How are you? You all right? You got some money get somethin' to eat?" Or somethin' like that. Never, "Gimme your ring. Gimmee your watch. Got any money?" Dad got hurt once. That's when they cut his arm. I think they pulled him in to some doors in some alleyway, cut his arm BIG. I got him to a hospital and they hadda stitch it up. He was never able to use that arm afterwards.

M: But that's the only dangerous thing that happened?

MM: Yuh. I pity them in the street now. Oh, they can come to Pine Street and they're sure to help 'em. They try to get you situated somewhere along the way. Pine Street's done a lot for everybody.

M: Would you have gone to a shelter?

MM: Oh, sure, if we knew there was one.

M: Tell me one more thing about talking to Dad every night. What do you say?

MM: Tell him to come back. Or be happy, I know he can't come back. (Little laugh.) I know he's happy with the Lord. We'll all be happy with the Lord. Still a long wait. I gotta strip some more.

M: So, what do you say to Dad at night?

MI: I miss 'im. I love 'im. Some sweet day I'll be there.

Millie Murray. 1990. She lived and worked as live-in staff in the Women's Unit of Pine Street Inn. Her husband, Tom, died in 1984. She died in 1994.

So now it's like, I don't have nobody there to tell me, well, this is how you gotta budget your money, you can only spend so much, you know. I never been through that because I used to pay room and board to my mother or room and board to whoever I slept with, you know what I mean? And they always provided the food. I never had to cook for me and my daughter or go food shoppin'. I go food shopping and it's like I buy everything I want and I can't afford everything I want, you know what I mean? See, I'm not into this, you know, this is my first time having my own spot, you know what I mean?

That's the only reason why I like this job, you know, because they get to go out places, and the homeless children as well as my own, they get to experience new things. They don't have to just stay in the park or stay in the shelter or go into some other project park, you know? They get to see things that they haven't seen. Go to the circus, learn about animals, things like that, you know that? They get excited off that stuff. That makes me feel good to see that a child is enjoyin' herself and because I'm a part of that,

you know, that makes me feel good. I never got to do them things when I was a kid, you know, but my kids aren't gonna live the life I lived. They gonna enjoy life, if I can help it.

My life sucked. Sorry. It sucked. I been drugged, deprived, and it hurts, you know. I'm happy because I have kids, you know, and my kids make me happy. There's nothin' else in this world 'cause my kids make me happy. I might be down and out because I'm stuck with them, but those are mine, and nobody will take that from me. As long as they're happy, I'm happy. (Laughs.) And vice versa. As long as I'm happy, they'll be happy.

Pat Gomes. Interviewed at the Salvation Army Day Care, Cambridge, where she was working part-time. 1989. She had her own apartment with her two children.

I think the biggest mistakes I've ever made was hitchhiking in the eighties. I've had some bad luck. I've been beat up, I've been attacked three times and raped. Um. There's been happy times, though, there's been a lotta happy times like, when I've stopped to work for a few years. I worked as a...maid and as a housekeeper, electronics, cocktail waitress, food waitress. I fell in love with somebody that's in a federal prison, but then I'm still not sure about love anymore. You know, What is it? It would be beautiful to settle down, but at the same time my other side of me says, "Why? You know, you're thirties, why don'tcha just wait and settle down when you're forty or somethin' like that?" Something' like that.

I still have my grandmothers. I hope that in the spring to go visit one. I'm really lucky in that aspect. A lotta people in the streets don't - have - their - their moms, and so I try not to bring mine up a lot. Not so much lost children, but Social Services has moved in or there's been a divorce. So, my story isn't - isn't really bad, yeah, I'm probably more curious - and really like bein' out in the outdoors. I'm more comfortable sleepin' out there under that tree than I am - in a bed. Have a lot of trouble sleeping which I probably can put towards the fact that I just quit booze. I drink in like spurts, like when I worked my last job, I didn't drink for four months.

The excitement, I think, behind, moving here on the east coast, is that I have only been on a subway once before--lookin' out the window and seein' all the lights--like last night, I looked out and saw a cargo ship--a cargo ship and airplanes--and it--it's neat. It--it's beautiful, and, that keeps me going, is to be able to look over--the ocean and see the lights at night and--and the sunrise, and seein' people like they laugh and they dance and--

"Janice." Interviewed at Long Island Shelter. 1988. Her father was in the Air Force. She left home at seventeen. She's been married twice and divorced.

The movie, "The Houses," you know, it isn't how people lived. They didn't live like that. People live, they live out in the street, they throw a blanket over'em and that's where they sleep. Ain't no such thing as somebody come and build a little hut for you to live in. No. None a that. I mean, without some help from somebody, people that are homeless are gonna stay homeless. I've been homeless for like four years now. Every time I get a little nest egg set aside, I get a place, well, my income from whatever job I'm workin' don't pay my rent. So, I'm back in the shelter again. Like now, I'm back in the shelter again. Again.

Sometimes I get, like, when you get on top of the Mystic River Bridge and play Charles Stuart, you know, I mean, what are we strugglin' for? Nobody else cares. Why should you care? You know? I gonna start cryin'. One thing after another. And it seems like the harder you try, the more you fall back. I mean, in Welfare, you know, they think they're doin' you a big favor, they give you $46.40, they give you $92.80 a month to live on. How could anybody climb out of a gutter on $92 a month? How much can you put away to get an apartment? You can't. It gets harder and harder instead of easier and easier.

You know, a lot of times, a lot of people in--what they call--institutionalized. What they mean by that is that they get so dependent on being homeless, you know, livin' in the shelters and livin' that kind of a life, they don't wanna leave. I guess after you do so long, you know, strugglin' tryin' to get outa it--you just give up all hope. But I got good old Italian blood in me and I'll fight until the day I drop. Catch me bein' institutionalized--baloney--I'm too much my own boss. I don't like nobody tellin' me what to do.

Judy Silva. Interviewed in Chelsea. 1989.

You get $32 every two weeks to live on. There's no way any homeless person can go out and buy their own food. You have to use this when you're homeless to be able to stay in a place. You can't just walk into a restaurant and sit. You have to get something, and then after an hour or so of stirring, people expect you're either going to leave or get something else.

[The shelter's] very much set up so you're of no use whatsoever. In the morning, you're asked to get out of the way so the tables can be set. And I've seen women try to help, especially people that have just come for the first time, and they're immediately [told], "No, no, get out of their way." And you get this everywhere you go, so all this does, as far as I can see, is just it's another reiteration and another reaffirmation that you're worthless, essentially. If you can't trade any service, you're also getting handouts and there's nothing more demeaning than to only be a recipient. Many of these women have to have skills of one kind or another. I don't know what they are, but I'm sure that if you were to just ask, "What can you do?"

Basically, anything you ever wanted to see again, you had to bring with you [from the shelter each morning]. You took everything, period, or it wasn't there when you got back. That was it. It was basically clothes. I do think that for women in particular, it went far deeper than that. It was almost as if the things one carried were oneself, as if one lost their identity without it. And yet that very same problem is what would keep anyone from getting out of the situation to begin with because you're burdened down with all this crap.

I stayed in the ladies' room at [a downtown hotel] for a number of nights. It was wonderful. It had a place to hang my clothes. It had a plug. It had a wonderfully comfortable chair and a very nice place to stretch out and sleep. All the amenities were there. And I'd just ask the doorman if he'd mind very much giving me a wakeup call at seven.

"Stephanie Hawthorne." Interviewed in her apartment, Back Bay. 1988. She was in her early fifties when I interviewed her. She had been married twice and possibly had ten children. She died a few years after this interview.