Pinhole

Nance could be dropped on the head of a pin and she'd have the angels dancing in neat rows by the next day and liking it, too.

She brings something practical to every friendship, as well as warmth and humor. She can find the specialist you need, an oncologist or a massage therapist, as well as tell you where to buy the best bagels. She's an expert at shopping, advising freely, nagging cheerfully. I am, I think, her only failure, having only worn the mauve linen suit once. When she and her husband moved to Arizona, a real loss in my life.

G. saves the postcards I send her when I'm away or need to tell her the day I'll visit. She has no phone in her room. We met when I worked at a shelter for homeless women. She's now a home health care worker and looks forward to retirement on social security.

She receives messages from God who reached down to save her from herself some years ago. The revelations are very complex. Often she writes them down, draws pictures to illustrate wheels within wheels or the brass idol with feet of clay. Occasionally she travels to distribute these teachings. She's been out to Utah and down to Florida since I've known her. The little glass donkey with a cart represents the ass pulling us out of the mire.

Since she was a little girl, my daughter has tried to improve things. When she was four or five, she'd climb onto the bathroom sink, pour out mounds of cleanser, scrub and sing commercials into the mirror.

When she was older, eleven or twelve, and had a little money, she'd buy things for the house. Once she bought a whole set of gray dishes, including two huge platters, at a yard sale.

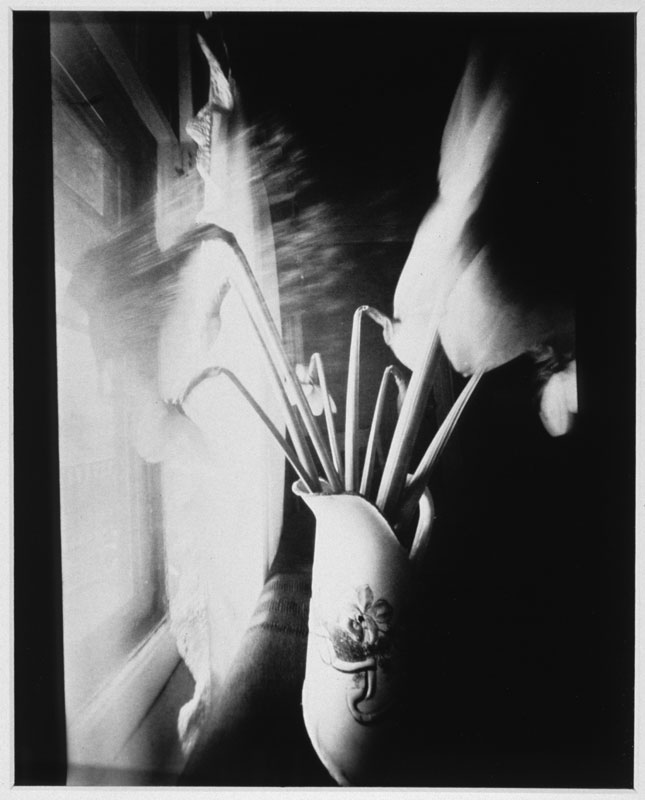

In high school, she bought a Mexican pitcher with six little cups. I'm sure she longed to live in a home where parties were frequent and Sangria was served.

My daughter's father was a star in college, a prized artist. He was one of the few to be given his own studio. Great things were expected of him.

He also had good taste. When he was living in Haight Ashbury, he'd buy a pair of $2 blue corduroy pants and they looked wonderful.

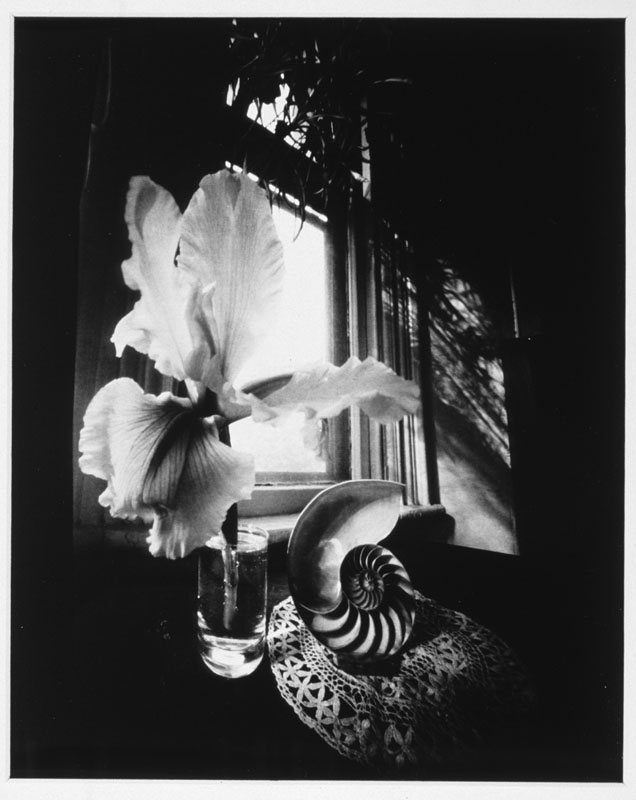

Later he'd send Krissy Christmas packages, numerous gifts wrapped in shiny paper with fancy ribbon, a red velvet box, an elegant shell with a clear plastic base for display. I gave her clothes, sweaters, underwear, socks, with some token gift in hopes of proving I, too, had a sense of style.

We were married the fall after I quit college and he graduated. I'd had the abortion the previous March and we stayed stuck together, undoubtedly succumbing to the influence of my step-mother. She truly believed no one would become pregnant unless she was in love. I left him near the anniversary of that abortion, taking little except a set of dishes and the little silver pitcher, wedding presents. He kept the apartment. I moved to a furnished room near Columbia.

Last summer, we had lunch when he came up to visit his daughter. He owns a country Inn. The woman he lives with runs it. Pewter, crystal, candles. His life is very different from mine, but he's a nice man, sensitive and kind. I never knew that, all those years ago.

This last year, I've been trying to find out about my mother. She's a mystery to me since I remember only fragments of my childhood before she died when I was twelve. I don't know what she looked like or what she did everyday, though I remember the house we lived in on Litchfield Road in great detail. Everyone I've spoken with said she had exceptionally fine taste and created a sparse but pleasing environment. There is little left from those years, a maple mirror, a small, plain round table with a broken edge, some heavy, rather ornate silver ware, tarnished brass bottom Revere cookware and a china rooster which stood on the shelf in the sunroom.

My mother was away in the hospital in Chicago on my 12th birthday, which fell on Easter. She’d bought candy and tiny china rabbits from Germany which my father must have put in the basket and left on the sideboard in the dining room. Raised as an agnostic, I had no understanding of this celebration except that it brought jelly beans, perhaps chocolate. Easter’s a dark time for me.

Nancy and I met when our daughters were in grade school. She was my first real friend in Boston. We’ve often shared holidays, always celebrated birthdays.

Four years ago she met Saul after searching long and hard for an interesting man. Last August, he went out for a bike ride early one Sunday morning, lost control on a hill and hit a car. He died the next day. It's still hard to accept that a man full of enthusiasm is gone.

I met Stephanie the year I worked as a coordinator in a shelter clinic. A witty, intelligent woman, she talked without drawing breath. Often she'd visit me, scattering belongings in the back examining room as she cleaned the spilled yogurt from her handbag, all the while telling stories of her adventures.

Sometimes I would take her into the clothing room where she'd pick out an evening dress, holding it against her long thin arms, checking the length carefully. She'd sort through the boxes of underwear and nylons until she found something satisfactory. Then she'd hunt for stiletto heels. That night she'd leave when the shelter closed, off to a bar in a fancy hotel to nurse one drink and read. Later, she'd sleep in the ladies room. In the morning, the doorman would knock to wake her.

Eventually she managed to gather enough cash for a two-bedroom apartment in Back Bay which she furnished with objects found in the alleys on trash day. Occasionally she gave me the cast-offs - a white table lamp with no plug, a brass floor lamp with a stained silk shade, a bicycle, two white directors chairs without covers, a little plate with the names of herbs on it.

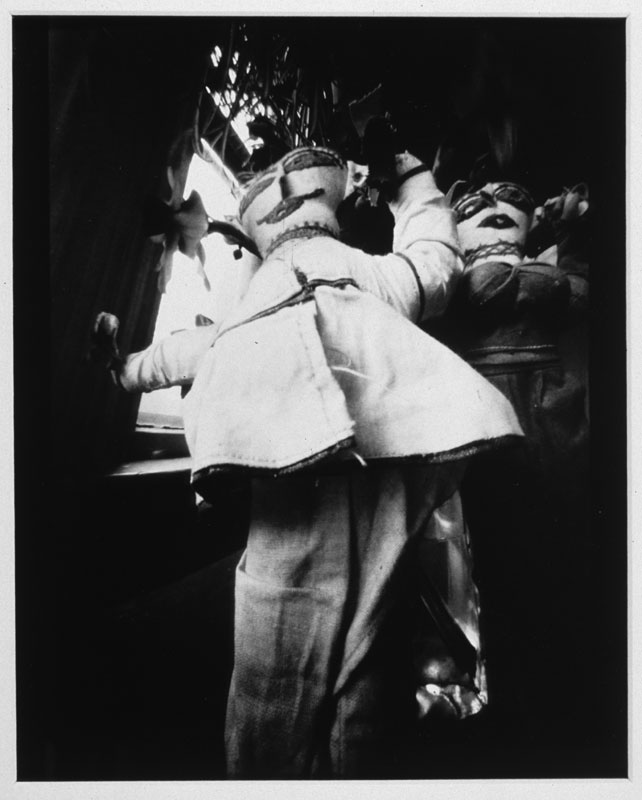

Without realizing, I set up a shrine to death with this mask and two little Mexican figures in my living room. Death has been a presence in my life since I was twelve and my mother died. There isn't a day I don't think about dying. A car accident on the Expressway seems always possible.

My father is almost 88 and has recently recovered from two serious illnesses, a stroke last year, an aneurysm four years before. On his last birthday, he announced that in thirteen years, he'll be 100. When I get home and there are numerous red blinks on the phone machine, I'm afraid there are messages about him.